.jpg)

Private Equity Insights

Darien Group exists to bridge the gap between exceptional design capabilities and private equity communications. Our library of resources serves as a practical guide for firms looking to refine or redevelop their brand and ensure their story resonates with target audiences.

Featured Videos

There is a predictable inflection point in the life of a private equity firm. Once a firm passes its first decade, the organization begins to accumulate layers of experience, sector depth, operational capability, and deal sophistication. What accumulates less visibly is narrative complexity. The firm’s self-description evolves informally across partners, deal teams, business development professionals, and the broader network of intermediaries and portfolio leaders. Over time, the language fragments. This fragmentation is rarely intentional, but it is inevitable.

Website revamps often serve as the diagnostic tool that reveals the underlying issue. They reintroduce a basic question that many firms have not confronted directly in years. What is the firm’s story, and is it being told the same way across all corners of the organization.

Narrative Drift as an Organizational Phenomenon

Within mature investment firms, narrative drift occurs gradually. Individuals refine their own versions of the firm’s origin, strategy, and differentiators based on their lived experience with transactions and stakeholders. These micro-narratives are not inaccurate. They are partial. Taken together, they create a diffuse understanding of the firm’s identity and value proposition.

Discovery sessions expose this condition with surprising clarity. Some team members emphasize the sourcing philosophy. Others focus on operational value creation. Others articulate the firm’s relationship with founder-led businesses. Each perspective reflects an authentic dimension of the firm, yet the absence of a synthesized framework means the story cannot be communicated consistently.

This is not a failure of messaging. It is a natural organizational phenomenon that occurs when firms grow without periodically re-interrogating the core narrative that binds them.

The Work of Synthesis

Once narrative drift becomes visible, the work shifts toward synthesis. The objective is not to impose uniformity, but to construct a coherent architecture of meaning. Through interviews with partners, junior investment staff, portfolio leaders, and external constituents, certain patterns emerge. These patterns are the raw materials for a unified narrative.

The art is in distinguishing what is central from what is incidental. Firms often describe themselves with reference to sector focus, partnership ethos, and differentiated capabilities, but synthesis requires determining which elements have strategic weight and which have become habitual descriptors. A strong messaging platform prioritizes what is empirically true, competitively relevant, and consistently reinforced by stakeholders.

In this sense, brand strategy functions as a form of organizational research. It surfaces, validates, and refines the claims a firm wishes to make about itself.

Why Website Projects Function as Brand Projects

There is a persistent misconception that a website overhaul is a digital exercise. In practice, the website is where strategic narrative, design systems, and organizational priorities collide. It requires decisions that cannot be deferred: what goes above the fold, what deserves explanation, what should be omitted, what constitutes evidence, and how directly the firm is willing to speak to founders or intermediaries.

The website becomes the moment where implicit assumptions must be translated into explicit choices. The resulting tensions are revealing. Firms often discover that clarity requires selectivity, and selectivity requires constraint. Many organizations resist constraint because it feels synonymous with exclusion. Yet in branding, the opposite is true. Effective communication requires the discipline to define and the confidence to stand behind those definitions.

A website is therefore not a container for existing materials. It is a forcing mechanism for institutional coherence.

The Interdependence of Design and Strategy

Design enters the process at the point where narrative becomes insufficient without a visual counterpart. A firm may articulate a thoughtful strategy, but without a modern design system, that strategy cannot be fully legible to external audiences. Conversely, design that lacks strategic grounding becomes decorative rather than interpretive.

The most effective branding work integrates the two through a reciprocal exchange. Strategy informs the creative range. Design reveals the implications of strategic choices by giving them form and spatial hierarchy. Over time, the narrative and the visual system converge into a single argument about how the firm understands itself and how it wishes to be understood.

This convergence is often the moment when internal teams first recognize the contemporary version of their own identity.

The Rise of Video as Empirical Evidence

As the market becomes more discerning, firms increasingly rely on video to function as qualitative evidence of their claims. Founder testimonials, operator perspectives, and portfolio narratives carry a level of authenticity that text alone cannot match. Video dissolves abstraction. It replaces assertion with demonstration.

For firms that work closely with founder-led or family-owned businesses, this shift is especially salient. The decision to select an investment partner is as psychological as it is financial. Video conveys tone, values, and interpersonal credibility in a way no written description can replicate. It is one of the few mediums that can show rather than tell.

What This Reveals About Branding in Investment Management

Taken together, these dynamics illustrate a broader truth about branding in private equity. The greatest challenges are not visual. They are epistemological. Firms must ask themselves what they believe, how they define their role in the market, and what they want their reputation to encode. These are questions that most organizations rarely confront directly until forced to do so.

Website revamps, brand updates, and messaging exercises create that moment of inquiry. They compel the firm to examine its own narrative structure and to bring coherence to the accumulated layers of its identity.

Early branding work often reveals the same fundamental need. Firms are seeking a structured, intellectually honest way to articulate who they are and how they create value. A strong brand provides that structure. It is not an ornament. It is a strategic framework that shapes expectations, guides communication, and enables the firm to present itself with clarity and confidence.

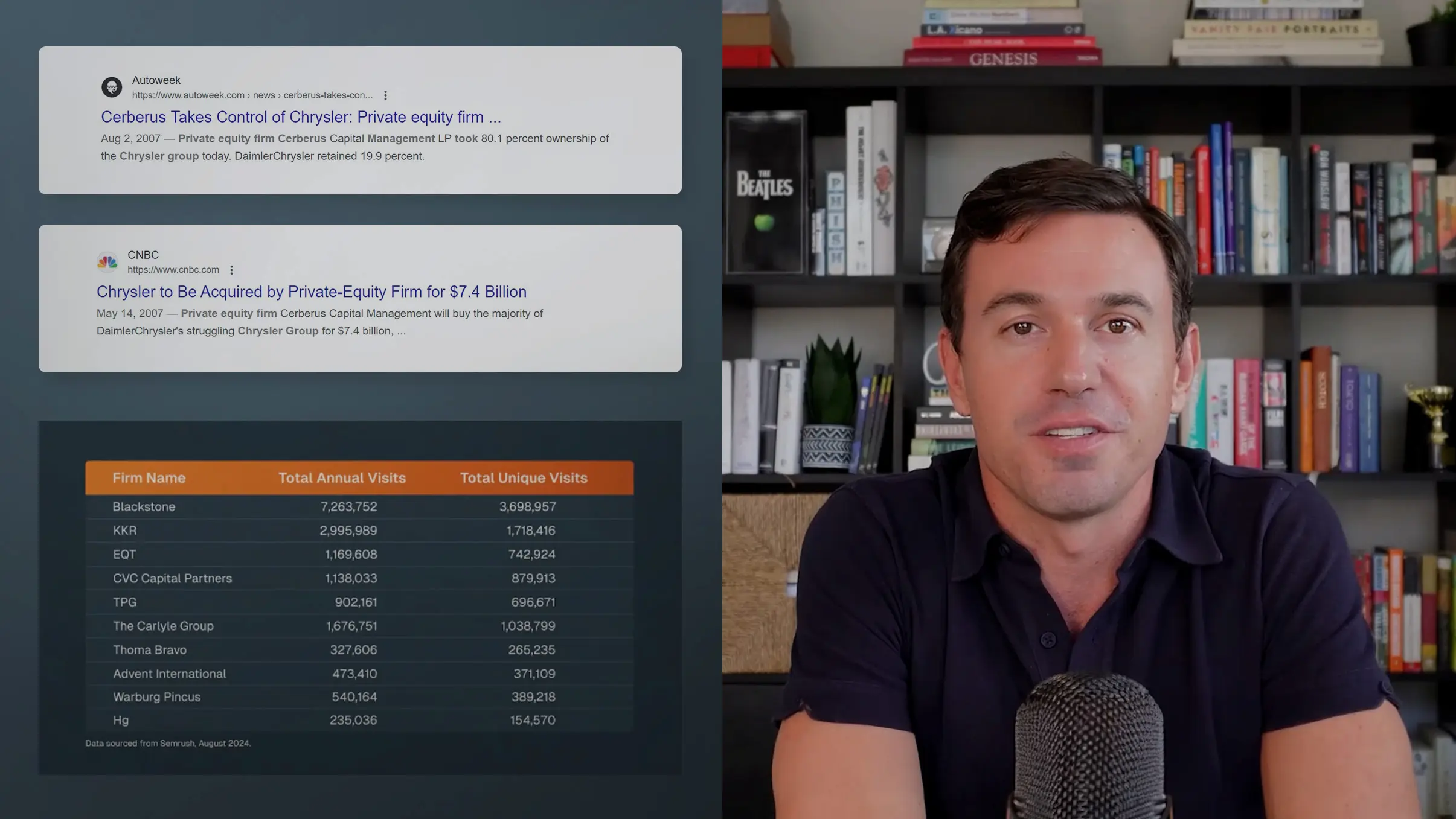

AI Is Now Embedded in Early Deal Work

As private equity looks toward 2026, artificial intelligence has moved decisively out of the “experimental” category. What began as pilot programs and isolated tools has become embedded in the way many firms approach early-stage deal work. According to Deloitte’s most recent global survey on generative AI in M&A, a majority of corporate and private equity respondents report active use of AI during strategy development, market analysis, target screening, and diligence preparation. Many of these firms are not testing at the margins — they are committing material annual budgets and expecting near-term operational impact.

This shift matters because it changes how preparation happens. Investment teams are using AI to review prior materials, summarize markets, compare targets, and assemble internal perspectives faster than before. Banks and advisors are doing the same. By the time a meeting is scheduled, much of the framing work has already occurred.

AI is not replacing human judgment, but it is shaping the starting point for it.

First Impressions Are Forming Earlier

The most important consequence of AI adoption is not speed, but timing. Evaluation is beginning earlier in the process, often before direct engagement. As AI tools ingest public-facing information — websites, firm descriptions, strategy language — they produce summaries and comparisons that influence where attention is directed.

Private Equity International has documented AI’s growing role across the private markets lifecycle, including fundraising and sourcing. In practice, this means firms are increasingly encountered first through synthesized views rather than conversation. Those synthesized views tend to reward clarity and penalize ambiguity.

By 2026, firms that assume their first real impression occurs in a meeting are likely to be surprised. In many cases, that meeting is already shaped by what was understood — or misunderstood — beforehand.

Why Context-Dependent Positioning Struggles

Many private equity strategies are nuanced by design. They reflect evolution over time, hybrid approaches, or subtle distinctions relative to peers. These narratives often work well in person, where explanation and dialogue fill in gaps.

They work less well when evaluated quickly and comparatively. AI-assisted review does not pause to ask clarifying questions. It extracts what is explicit and moves on. Positioning that relies on implication or assumed familiarity can be flattened or misread.

This does not mean firms should simplify their strategies. It means they should articulate them more deliberately, with fewer assumptions about what the reader already knows.

What Firms Should Be Adjusting Now

The firms adapting most effectively are not increasing volume. They are tightening expression. They are refining how they describe their mandate, where they sit in the market, and what they prioritize — so that those ideas hold up even when read without explanation.

AI has not changed the fundamentals of private equity judgment. But it has moved the point at which judgment begins. Firms that adjust for that reality will find conversations starting further along.

Many investment firms are built on discretion. For years, that discretion is not just appropriate — it is essential. Capital is concentrated, relationships are curated, deal flow is controlled, and visibility is something to be managed carefully, if at all. In that context, brand is not a growth tool. It is a risk-mitigation exercise.

The challenge arises when the firm evolves, but the assumptions behind that discretion do not.

At a certain point—often five or more years into a platform’s life — the operating reality changes. Capital formation becomes more outward-facing. Talent acquisition becomes more competitive. Access to differentiated opportunities requires signaling, not silence. What once felt prudent can begin to feel constraining. And yet many firms continue to evaluate their brand, website, and materials through a lens that no longer matches where the business is going.

This is where marketing conversations become difficult, not because change is unwelcome, but because the foundations were never built to support it.

The Risk of Treating Brand as Cosmetic

When firms decide to “do something” about their public presence, the instinct is often incremental. Add the team page. Publish a few news items. Increase LinkedIn activity. Refresh imagery. None of these moves are wrong, but they are rarely sufficient on their own.

The issue is that most brands are not weak at the surface level — they are incoherent underneath. Names, color palettes, typography, imagery, and tone are often the product of historical convenience rather than strategic intent. Decisions were made quickly, internally, and for reasons that had little to do with how the firm would eventually be perceived by external audiences.

Those decisions calcify. Over time, they become difficult to challenge, even when everyone senses that something is off.

A website redesign layered on top of those assumptions does not fix the problem. It simply makes the misalignment more visible.

When Strategy Changes, Brand Has to Catch Up

One of the clearest signals that a firm has reached an inflection point is a shift in how it thinks about capital. Firms that have historically operated with captive or highly concentrated capital pools often have very different branding needs than firms pursuing broader, more traditional capital formation.

Discretion gives way to explanation.

Insulation gives way to comparison.

Silence gives way to narrative.

In those moments, brand stops being about what you avoid saying and starts being about what you stand for. That requires testing assumptions that may have gone unquestioned for years: Does the name still work? Does the visual identity communicate the right balance of credibility and ambition? Does the website reflect what the firm actually does — or what it did when it was founded?

These are not aesthetic questions. They are strategic ones.

Why Patchwork Fixes Create Long-Term Friction

A common temptation is to fix the most visible gaps first: patch up the pitch deck, reskin the materials, update PowerPoint templates. These are often urgent needs, especially for firms that are beginning to engage more actively with LPs, intermediaries, or partners.

The problem is sequencing.

When materials are rebuilt inside an outdated or ill-defined brand system, they almost always have to be redone later. Color palettes no longer align. Typography changes. Messaging evolves. What initially felt like momentum turns into rework.

This is why foundational brand and messaging work matters, even for firms that are not seeking reinvention. The objective is not to change everything—it is to determine what should change, what should stay, and why. Without that clarity, every downstream asset becomes provisional.

Brand Is Not About Changing for the Sake of Change

The most effective brand engagements are not driven by a mandate to overhaul. They are driven by a willingness to interrogate.

Why this color?

Why this tone?

Why this imagery?

Why this level of visibility?

In some cases, the answer may be that a decision still holds. In others, it becomes clear that a choice made for internal reasons no longer serves the firm’s external goals. The value of a structured brand and messaging process is not that it guarantees change, but that it replaces intuition and legacy bias with informed judgment.

Once those judgments are made, everything else becomes easier. Website decisions are no longer debates. Pitch decks are no longer exercises in compromise. Content has a point of view instead of a checklist.

Doing More With Less Content

Another reality for many firms at this stage is that they do not yet have a large volume of public content. Deal cadence may be measured. Disclosure may be selective. Thought leadership may be emerging rather than established.

This is where experience design becomes critical.

A compelling website does not require dozens of pages or constant publishing. It requires structure, hierarchy, and clarity. Strong UX, intentional layout, and well-considered messaging can make limited content feel substantial and memorable. When done well, the site communicates confidence without noise.

The same principle applies to materials. A disciplined narrative, paired with clear visual systems, can carry a firm far further than volume ever will.

The Cost of Waiting Too Long

Firms often delay these conversations because they fear disruption — internally and externally. Ironically, the greater risk is letting outdated assumptions persist while the business moves on.

Brand systems last a long time. Websites live for years. The decisions made today will shape perception well into the future, whether intentionally or not. At inflection points, the question is not whether change is required, but whether it will be proactive or reactive.

Firms that take the time to step back, test their assumptions, and build a coherent foundation tend to find that everything downstream becomes simpler, faster, and more effective. Not because they did more — but because they did the right things in the right order.

Most emerging managers think design in a pitchbook is about aesthetics — color choices, layout, typography, the general look and feel. LPs don’t experience it that way. They don’t evaluate pitchbooks on beauty; they evaluate them on intent. Design becomes a form of pattern recognition: a quick way to assess whether the GP is organized, credible, and attuned to institutional expectations. Design is not the wrapper around the story. It is the first operational artifact an LP encounters, and it tells them far more than most managers realize.

1. Design Signals Whether the GP Understands the Institutional Environment

LPs have seen thousands of pitchbooks. They know what a mature deck looks like, and they know what an improvised one looks like. When a deck feels under-designed or oddly assembled — misaligned charts, inconsistent fonts, clashing iconography — LPs instinctively read that as a lack of institutional fluency. They don’t think, “This is ugly.” They think, “This manager hasn’t quite internalized the norms of our world.” That inference may be unfair, but it is reliable. Design is not just visual styling; it is an indicator of whether the GP knows the rules of the professional arena they’re entering.

Emerging managers sometimes underestimate this because they have worked in environments where someone else handled the brand infrastructure, and materials arrived pre-structured. When they go solo, they realize how much design literacy they had been absorbing subconsciously. LPs can tell when that literacy is missing.

2. Overdesign Is as Damaging as Underdesign

If one group of emerging managers errs on the side of minimalism, another group errs on the side of ornamentation — especially in real estate. They want the deck to look like a gorgeous property brochure because that’s what they’re used to seeing in the marketing of assets. But a glossy, hyper-stylized pitchbook does not communicate what a fund pitchbook needs to communicate. It doesn’t say, “We are serious stewards of institutional capital.” It says, “We know how to market assets,” which is a different skill entirely.

On the private equity side, overdesign appears in subtler ways: too many color gradients, heavy motion-like effects, fonts that feel like they belong in a consumer brand rather than in institutional finance. These are distractions, not advantages. LPs don’t want to think about design; they want design to make thinking easier.

Good design in a pitchbook is invisible. It creates clarity without calling attention to itself.

3. PowerPoint Is Not a Limitation — It Is an Expectation

Every now and then, a new manager will ask us to build their pitchbook in InDesign because they want it to look “more premium.” And yes, InDesign can produce beautiful documents. But these requests are almost always rooted in misunderstanding. LPs expect pitchbooks in PowerPoint because PowerPoint is editable, familiar, and legible in the context of diligence. A deck that is too glossy or too static can feel like it’s trying to compensate for something. LPs want substance, not spectacle. The format shouldn’t be the memorable part.

This is not to say pitchbooks should be plain. They should simply be aligned with what the category expects. In an emerging manager context, memorability should come from the ideas, not the packaging.

4. Consistency Across Materials Is a Signal of Organizational Maturity

LPs don’t evaluate your pitchbook in isolation. They triangulate it with your website, your bios, your data room, and even your email signature. When these elements are aligned, they signal discipline. When they are not, they signal drift. A pitchbook that looks one way while the website looks another forces the LP to reconcile two versions of the same firm. Most won’t bother.

This is especially true when the deck’s tone diverges from the website’s tone. If the deck is conservative but the website is modern, or the deck is overly technical while the digital presence is clean and straightforward, LPs interpret that inconsistency as a lack of self-understanding. In reality, the GP may simply be iterating quickly. But to LPs, it reads as fragmentation.

The pitchbook is where narrative and design converge most visibly. When it matches the rest of the firm’s digital ecosystem, LPs feel the underlying cohesion. When it doesn’t, they feel the instability.

5. Poor Design Doesn’t Make You Look Unattractive — It Makes You Look Unready

Emerging managers often think bad design will make them look unsophisticated. That’s not the real issue. Bad design makes you look unready. It signals that the GP has not taken the time to structure their story, their visual system, or their materials in a way that supports institutional evaluation. Even something as simple as a mismatched chart or a slide that feels “borrowed” from an old deck sends a quiet signal: this manager is still assembling themselves.

LPs may not consciously register these cues, but subconsciously they draw inferences: If the deck is disjointed, is the process disjointed? If the exhibits are sloppy, are the underwriting memos sloppy? If the narrative is unclear visually, is it unclear operationally? None of this is determinative. But all of it is suggestive.

Emerging managers underestimate how quickly these inferences form and how slowly they dissipate.

Closing Thought

Design in investor materials is not cosmetic. It’s structural. It shapes how LPs absorb your story, how they interpret your maturity, and how they assess your readiness for institutional capital. The goal is not to impress; the goal is to make the narrative unmistakably clear. When a pitchbook feels intentional, coherent, and appropriately restrained, LPs assume the same about the underlying firm. And for emerging managers, that assumption is often the bridge between being viewed as “interesting” and being viewed as “investable.”

There is a juncture in the life of a private equity firm that does not appear on the org chart or in the fundraising timeline, yet it carries enormous strategic weight. It arrives when the internal complexity of the firm surpasses the simplicity of the story it tells about itself.

We see this most clearly in firms that have evolved beyond a single investment style. They add new strategies, expand operator networks, pursue more creative transaction structures, or institutionalize their team. Internally, the firm becomes sharper and more sophisticated. Externally, it still communicates like the earlier version of itself.

The result is an informational mismatch.

This article examines the specific scenarios in which this happens and why the solution requires more than new language. It requires a restructured mental model of how the firm explains itself to the outside world.

1. The Multi-Strategy Drift: When a Firm Builds Two Engines but Describes Only One

A common pattern appears when a firm that built its reputation through platform investing adds a second engine. It might introduce:

- an asset-level solutions strategy

- a structured capital sleeve for operators

- a secondary program designed to purchase equity at a discount

- a co-investment structure that complements the core strategy

Inside the firm, these strategies share logic. They draw on the same operators, the same information pathways, or the same pattern recognition.

Outside the firm, they appear unrelated.

The typical scenario looks like this:

- A firm’s asset-level work depends on insights drawn from its platforms.

- Its platform work benefits from relationships created through solutions-oriented capital.

- Its team learns across strategies in ways that accelerate underwriting.

Yet the external materials describe these strategies in separate silos. The audience cannot see the relationships, so the firm appears more fragmented than it is.

This fragmentation is not a branding problem. It is an architectural problem.

2. The Operator-First Reality: When Your Competitive Advantage Is Invisible Externally

Many firms derive real advantage from their operator relationships. Operators provide early visibility into opportunities, real-time context on market conditions, and nuanced feedback that strengthens underwriting.

Yet this operator-centered model rarely appears in firm messaging. Instead, communication defaults to fund size, sector focus, and geography.

We often see a scenario like this:

A firm sources half its best opportunities from operators long before intermediaries circulate them. Its diligence processes rely on direct conversations with management teams who trust the firm’s approach. Its multi-year relationships lead to repeated opportunities within the same network.

But none of this shows up in the firm’s external explanations. The operator network is treated as incidental rather than central.

Once articulated clearly, this advantage reshapes how intermediaries engage, how operators reach out, and how LPs interpret the strategy. A firm is not differentiated by the existence of an operator network but by the meaning of that network within its investing model.

When the firm finally explains this clearly, the market recalibrates its understanding.

3. The Maturity Gap: When an Institutional Firm Communicates Like an Early-Stage Firm

As firms scale, they adopt new structures. They introduce investment committees, create value-creation frameworks, develop internal reporting cycles, and build differentiated roles across the team.

Yet externally, the firm may still present itself as a small specialist with a simple model.

This creates a misalignment with consequences:

- LPs cannot fully see the sophistication that now exists

- Operators underestimate the firm’s ability to support them

- Candidates misunderstand what the role will require

- Advisors send opportunities that do not match the evolved mandate

The firm operates at a higher level than its communication suggests. The gap between internal structure and external messaging becomes a source of inefficiency.

The firm is, in effect, outgrowing its own story.

4. The Understatement Paradox: When Restraint Collides With Institutional Expectations

Many firms prefer a restrained identity. They value discretion, focus, and a low-contrast style. They resist anything that feels promotional.

This preference is deeply rooted in the middle market.

However, restraint does not eliminate the need for clarity. It simply constrains the methods available to provide it.

We often hear something like this:

A firm wishes to remain understated while also wanting better recognition among operators, clearer articulation of its strategies, and materials that reflect its maturity.

This is not a contradiction.

It is a structural challenge.

Understated firms do not need more noise. They need sharper explanations. They benefit from organized information, precise framing, and communication that mirrors their temperament without diminishing their sophistication.

5. The Missing Framework: When Everything a Firm Says Is Correct but Not Connected

Many firms share accurate details about themselves. They describe sectors, strategies, geographies, team backgrounds, and values.

Yet what the audience is seeking is the foundational idea that connects these components.

For example:

- A firm may appear diversified across nine asset categories, when in reality its exposure reflects a highly focused operator sourcing model.

- A firm may appear geographically scattered, when in truth its operators create a unified map of where demand exists.

- A firm may appear to run unrelated strategies, when the strategies reinforce one another in ways that improve decision making.

The facts are sound. The interpretation is incomplete.

Without a framework that explains how the parts relate, the message relies on the audience to infer the structure, and most will not.

Conclusion. The Most Strategic Firms Rebuild Their Message When Their Structure Evolves

Private equity firms change. They implement new strategies, deepen relationships with operators, enhance internal processes, and refine their investment discipline. What often remains unchanged is the external message that once served the earlier version of the firm.

Eventually, the firm reaches a point where the old message obscures the current strategy. The organization becomes more sophisticated, but the communication remains static.

The firms that address this inflection point do not simply revise language. They reorganize how they explain themselves. They establish a structured foundation that accurately reflects the firm's actual design. They make the internal logic visible and accessible.

A firm that communicates its structure with precision is interpreted with precision. A firm that expresses its model clearly is understood quickly and accurately. A firm that reorganizes its message to match its evolution operates with fewer barriers and greater momentum.

Private equity and alternative investment firms often come to us at the exact moment when their brand foundation is starting to feel too narrow for where the firm is heading. In these early conversations, we hear a familiar mix of excitement and uncertainty. Some clients arrive with a few potential names already chosen. Others have no formal collateral at all. Most know exactly how they want to be perceived, but are unsure how to translate that into a name, identity, and digital presence that feels intentional, credible, and lasting.

These discussions often surface deeper strategic questions. How should a new firm position itself relative to its legacy. How do you craft a visual identity that feels distinct without drifting into abstraction. How do you build a website that supports fundraising and deal conversations at the same time. Over the years we have noticed patterns in how successful firms navigate these decisions.

This is a look behind the curtain at the conversations that shape a brand before any pixels or pages exist.

Why Naming Is a Strategic Exercise, Not a Creative Guessing Game

We have had many founders say something like, “We have three names we like. Can you tell us which one is strongest.” What they are really asking is whether their instincts align with how the market will interpret the name. We see this across nearly every naming engagement. The debate feels tactical, but the underlying questions are philosophical. What makes a name credible. What makes it durable. What will it signal in a room full of LPs or founders.

We have written before about how naming actually works in investment management, and why the search for the perfect name is often a distraction from the decisions that matter. Read more in our piece, The Myth of the Perfect Name in Investment Management.

Our own experience has shown that naming is not a subjective preference exercise. It is a strategic filter. The categories we explore during discovery determine the types of names that make sense for the firm. The name chosen should reflect how the firm wants to be understood by investors, founders, and partners for years to come.

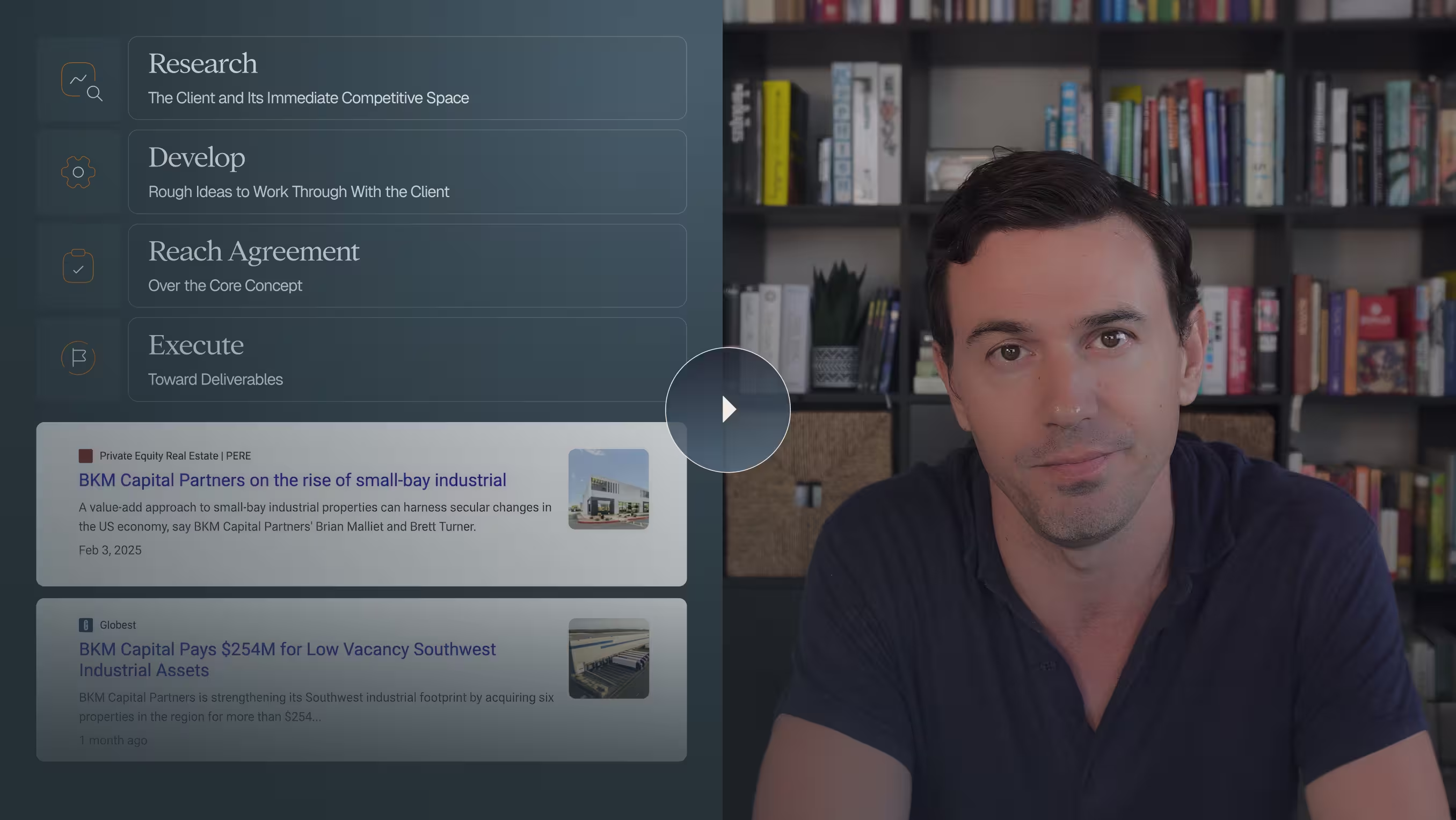

The Branding Process Firms Respond to Most

Many private equity firms initially approach branding with a desire for speed. They quickly learn that momentum requires structure. When we outline a typical process, clients often say this is the first time branding has felt navigable.

The progression matters. Conversations during discovery shape the takeaways that inform early positioning. That positioning informs creative direction. That direction shapes the first versions of the homepage. Those prototypes give structure to the written narrative. Each step compounds the previous one and reduces revision cycles later.

Firms often tell us that this stage is where they finally see their story reflected back with clarity. The language begins to align with the identity they want to project. The early visuals define the posture they intend to occupy in the market. Branding is not a linear checklist. It is a sequence of calibrations.

How PE Firms Should Think About Website Strategy During a Brand Build

In nearly every early meeting, we hear a version of the same request. A firm needs a first-phase website ready for a capital conversation, or a homepage that can support active deal sourcing. The tension is familiar. Firms want the long-term brand to be thoughtful, but they also need something credible in the near term.

The solution is structured sequencing. We often begin with strategic website planning, even before the full identity is complete. This includes page hierarchy, story architecture, and functional planning. Once those decisions are aligned, we create an interactive prototype that lets the working group experience the site before development begins.

Clients consistently say this is one of the most clarifying steps. Seeing the site in motion, even in grayscale, helps them understand how the brand will behave digitally. It also compresses future revisions because structure, flow, and messaging are already aligned.

What Firms Can Prepare Before a Brand Engagement Begins

Some teams have a library of strategy decks and positioning language ready to share. Others have only a broad idea of how they want to present themselves. Both starting points are workable. What matters more is assembling the reference points that help tune early creative decisions.

Screenshots of sites they admire. A list of attributes they want the brand to convey. A few inspirational materials saved over the years. These clues provide direction for creative range finding and avoid unnecessary exploration.

More important is early access to leadership. Five or six hours of interviews across senior partners, junior team members, and operational leads often produces sharper insights than any written document. Those themes become the foundation of the brand.

The Less Visible Work That Ensures a Smooth Brand Build

Clients often assume the most challenging work lies in the creative expression. In reality, the leverage comes from the operational details. Clear working-group structure. Defined decision-making protocols. Predictable handoffs between strategy, design, and development. A shared Dropbox environment for materials. A scheduling process that eliminates friction.

When firms reflect on successful brand projects, they rarely point to a single deliverable. They point to the experience of the process. They describe predictability, clarity, and momentum.

What These Conversations Tell Us About Successful PE Branding Today

Private equity branding is changing. Firms value substance over theatrics. They want names that reflect intent. They want websites that guide LPs and founders toward meaningful conclusions. They want identities that feel modern and calibrated to their worldview. And they want narratives that reflect the seriousness of their work.

Early branding work often reveals the same underlying desire. Firms want a structure that helps them understand themselves with precision. A strong brand is not decoration. It is a framework for how a firm shows up in the world and the expectations it sets for its partners.